Our hometowns leave an impression. They help us define ourselves, for good or ill. My hometown of Santa Fe, NM was like a faceless fifth member of the family. I alternated between hating it and loving it, like a sibling who read my diary and then gave me a thoughtful birthday present. Its alternate routes, and hidden alleys and beautiful views and eccentric homeless citizens made for an adventurous childhood.

Our hometowns leave an impression. They help us define ourselves, for good or ill. My hometown of Santa Fe, NM was like a faceless fifth member of the family. I alternated between hating it and loving it, like a sibling who read my diary and then gave me a thoughtful birthday present. Its alternate routes, and hidden alleys and beautiful views and eccentric homeless citizens made for an adventurous childhood.

It was a good place to grow up and a horrible place to grow up. It had awful schools, which I miraculously avoided one way or another, and an intense friction between the Latino, White and Native American populations. It also had the richest cultural life in America, with a fascinating history and artists in every other house. Its winters were cold and snowy. Its summers were hot and dry. Its springs were rainy, the air filled with the smell of oncoming storms. There was a silence that spoke to you. There was poverty that could take your breath away.

It’s incredible that we all see these elements in our hometown. Maybe you grew up somewhere that was the exact opposite from where I did. A rural town maybe. Or a big city. But I bet you had the same extremes, and I bet they helped define you and how you see the world around you.

I was lucky. I ended up loving my hometown. I still yearn for it and all it promises. I see where it falls short, and I still love it. But so many people I know can’t stand where they came from. They’re out and they’re never going back. I wanted to explore that dynamic in a Shirley Link book to better understand it. I also wanted to tell a story, a hopeful one, to kids who are struggling with where they are.

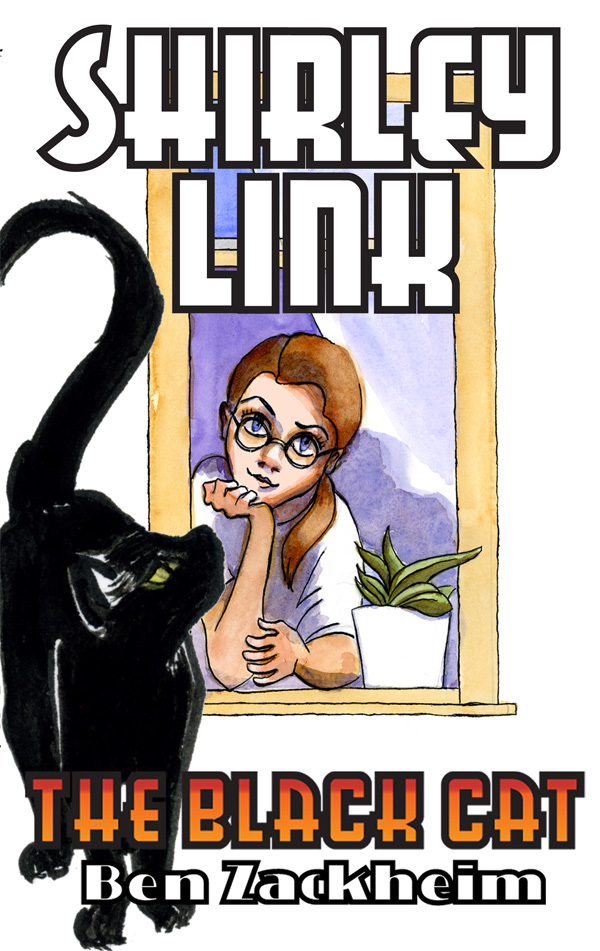

In Shirley Link & The Black Cat, a young man, 17, and his girlfriend, also 17, are the prime suspects in a string of robberies. There’s very little evidence, if any, that they did anything wrong. But that doesn’t stop everyone, even Shirley for awhile, from jumping to conclusions. I tapped into a deep sadness as I wrote about them. They were flawed — mean, odd, petty. But they were that way for a reason. They’d constructed incredibly complex and effective weapons against their community, which, for whatever reason, decided they were outcasts. And they found each other so they could have something in their lives that wasn’t mean, odd or petty.

As I wrote this growing up story I rooted like hell for them. I didn’t know what would happen. It wasn’t mapped out. In the end, I depended less on my need for a happy ending than I did on my ever-developing sense of what we need from our youth. We need support and understanding. We need company. We need community. Either our family, school and hometown provides these things or they don’t. And if they don’t? My conclusion is that we still gravitate toward what will make us feel kind, loved and understood.

It made for the most realistic adventure in my middle school reader series. There are no pirates, or magic safes, or valuable comic books. Just two teens caught in a mess. And a fourteen year old amateur sleuth who wants to help, and who grows up a little bit in front of our eyes.

by Ben Zackheim