by Ben Zackheim | Sep 12, 2014 | The Camelot Kids, Writing |

Chivalry is the act of defending those who cannot defend themselves.

That’s a simplification, but I’m going with it (for now), and you can’t stop me.

The same way magic is the code that holds Harry Potter’s world together, chivalry is the code, the foundation and the social dynamic of Camelot.

Now that I’ve completed Book One, I understand that something in the core of the mythology was drawing my own sense of chivalry out of me. It was injecting these complex, flawed characters with a sense of doing the right thing, no matter the cost. Sure, the complex moments of bravery, stubbornness and kindness were emerging in a mystery/action/adventure yarn. But within the mask of story was a seed of humanity that I’d never considered deeply for my protagonists before.

An orphan helps an orphan.

A bullied student helps the new kid escape a gang.

Even those who live a life rife with heartache and hard knocks emerge chivalrous. No, especially those who live a life rife with heartache and hard knocks emerge chivalrous.

But why? How? Where does this instinct to protect those around us come from? What happens inside us when we drop our own interests and risk everything for other people?

The answer became clear as I wrote the book.

The dynamic of wanting to connect with people is the same dynamic that makes us risk everything to help them. In other words, our connection to each other, simply because we’re human, has costs as well as payoffs. For our humanity, we get friendship, love and support as a “payoff”. But does that mean that heartbreak, pain and rejection are the “cost”?

No. That was my revelation as I wrote The Camelot Kids.

The cost of this human experience isn’t heartache, pain and rejection. It’s chivalry.

Being loved, supported, hated, ignored creates an astonishing power to do the right thing for anyone — friend, foe, or stranger. That human connection is so complex that something in us is willing to give our lives for it in a split second.

For me, this revelation does something profound to my sense of modern life. Don’t we live in an insulated bubble? I’ve assumed that most of us reach a certain age of reason where we construct a world with as much love as possible, and avoid the most pain. It takes a while, but it seems to me to be a standard human thing to do. To the degree that we have control over our surroundings, don’t the vast majority of us expend a tremendous amount of energy on building comfort and avoiding discomfort?

While I still think the answer to these questions is yes, it’s clear that we have a Trojan horse of bravery, duty, kindness and chivalry in us. It’s rolled into our gut at around the same time we look at another human and realize we want to keep them close forever. And it’s solidified when we meet our first enemy.

I think it’s the most exquisite insight we could have today. I think mythology that reinforces this inherent power in each of us is what we all need right now.

Taking this idea further; our disillusionment with Arthurian lore is indicative of our disconnect with our own chivalry.

Prove it!

Okay. When was the last time we felt connected to the second most famous myth of our time? We get chance after chance in the Merlin or Camelot TV shows, the recent King Arthur movie — but they don’t resonate outside a small group of fans. It’s not because the efforts suck, necessarily (though some do). It’s that they’re stale. They treat chivalry like it’s a noble thing only, and not the complex force it is.

Chivalry is Gandhi.

Chivalry is Martin Luther King, Jr.

Chivalry is Malala Yousafzai.

The heroes of Camelot don’t need to tell the same thousand year story again.

The heroes need to be among us. More importantly, they need to be chivalrous among us.

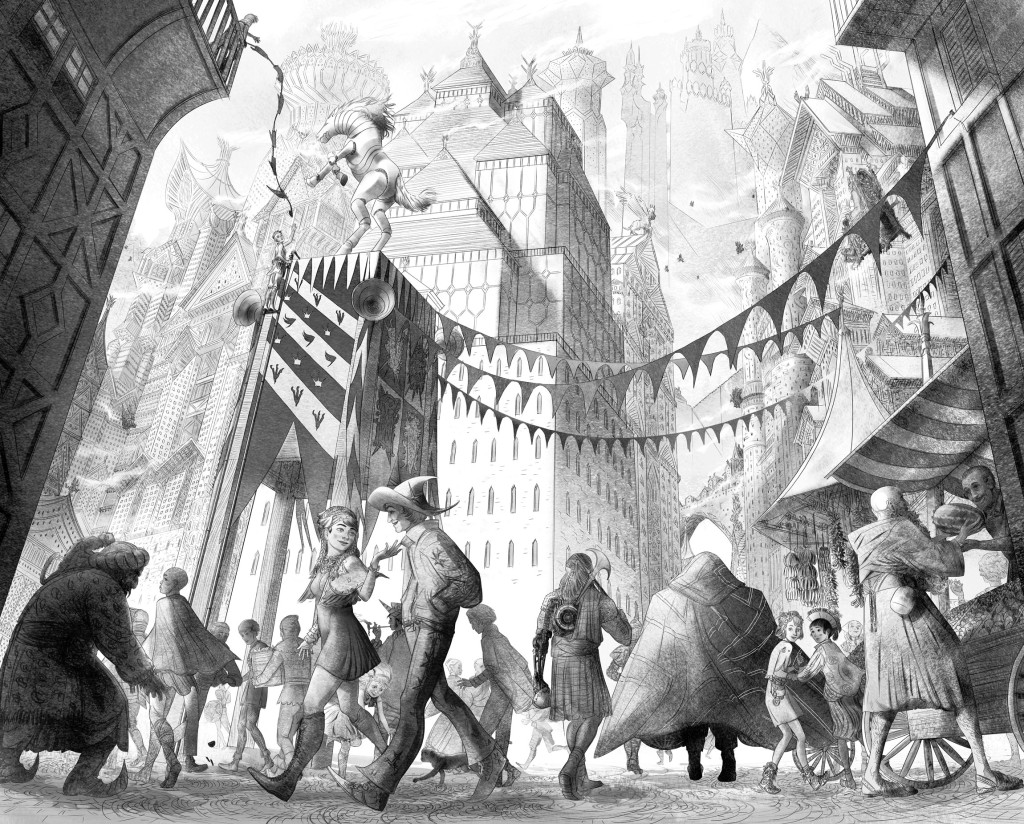

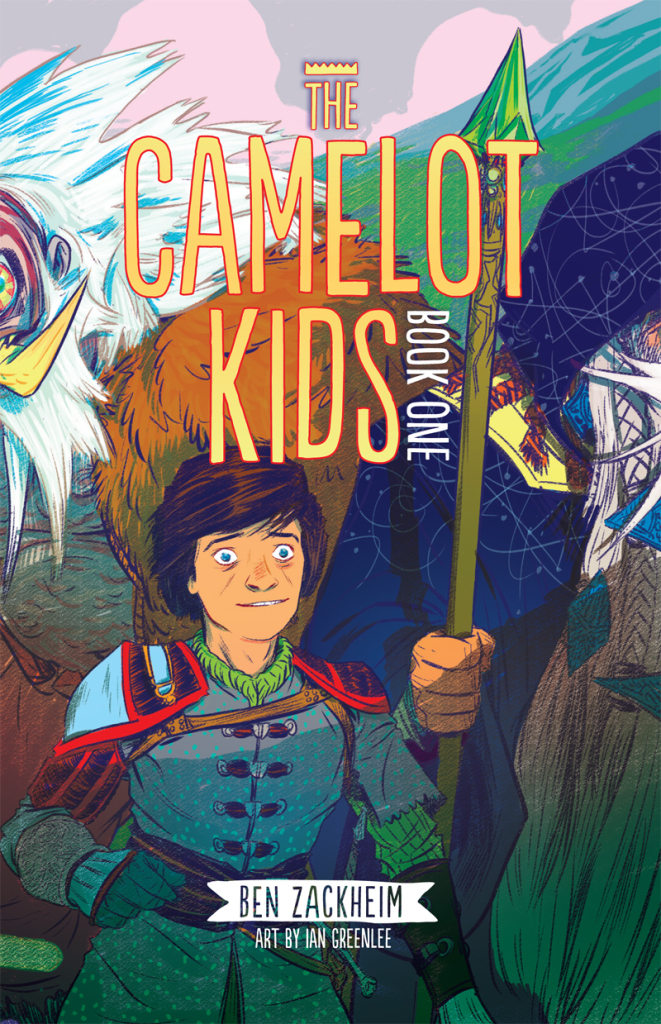

So for all my humility and fear in tackling the lauded lore, my goal with my new book, The Camelot Kids, is to give the world a peek into Camelot in our time. I want to make Camelot fun again. And I want to do it in a way that’s respectful of the tales’ whimsy, boldness and deep conviction that to do right for others is to do right for everyone, including yourself.

After all, the more in touch we are with our inner Camelot, our sense of chivalry, the better off the world will be.

by Ben Zackheim | Jul 28, 2014 | Writing |

I’m not sure why Goodreads hides their “Add a New Book” page from us. Are they afraid of some kind of literary hack? Or an avalanche of white papers? A storm of porn? Whatever the reason, just try to search for “add my book to goodreads” and you’ll find what you’re looking for waaaaaaay down on the search results page.

All you have to do is go to this url, and you’re set:

Add my book to Goodreads

Simple post for a simple process. Made hard by Goodreads.

Good luck!

by Ben Zackheim | Jun 28, 2014 | The Camelot Kids, Writing |

Twitter

(Please click the Retweet icon at the bottom of the post below)

Facebook

(Please Share or Like a Facebook post)

If you’re not seeing Share or Like buttons in the post above, then you can click on these links and share from there!

Pinterest

(Please pin this image to one of your Pinterest pages)

Follow Ben Zackheim’s board The Camelot Kids on Pinterest. [divider divider_type=”dark”][/divider]

Take the quiz and share your result!

(Which Camelot character are you? Please share your results on Facebook)

by Ben Zackheim | Jun 19, 2014 | Writing |

How to price your ebook can be a tough decision.

Which is surprising since there aren’t many standard price points to choose from!

$.99 – $9.99

That can be broken down in fifty cent increments or one dollar increments. ($1.49, $1.99, $2.49, etc.)

Sure, you could charge $1.27, or $6.73, but price points like that tend to make customers think they’re buying a used item.

So with a max of 19 prices, how do you price your ebook?

What does the competition charge?

Get a clear picture of what people expect to pay for your kind of story.The best place to start is to look at what the competition charges in the Top 20, then price-match the books that you’d like to compete with.

For those of us who write in those annoying little gray areas where it’s tough to find the competition… well… we need to dig a little deeper to find good facts to work from.

My Shirley Link mystery series for Middle Grade to Young Adult is a perfect example. Not many indys write in this specific category, which makes it hard to price match with competitors. I’ve found that most people just won’t pay a Nancy Drew price for an indy book.

Not enough competition to price-match? Try, and try again!

After a lot of trial and error, I’ve settled on my latest pricing strategy of:

Shirley Link & The Safe Case (#1): FREE

Shirley Link & The Hot Comic (#2): $.99

Shirley Link & The Treasure Chest (#3): $2.49

Shirley Link & Black Cat (#4): $2.99

It’s a cross between the pricing strategy of Romance ebooks and Kids ebooks. Start free, make #2 cheap, then crawl up to $2.99, where I can start to make some good money.

Frankly, it’s been a tough road to find the right price for Shirley Link! But I’m definitely getting closer as I try different prices and roll out new books.

Should I go free?

Perma-free is the term we use to describe a book that is free “forever.” Many series authors make the first book in the series free because it helps increase visibility. Going perma-free, when done right, can mean higher sales for the rest of your series.

If you write a series, then do the following to decide if you should go perma-free on Amazon.

1) Do 3 Free Promo Days with book #1.

2) Measure the sales of the entire series post-promo.

3) Answer this question: If your entire series did this well all the time would you be happy? If the answer is yes, then ask a follow-up question. Would you be happy if your series did half as well all the time? If the answer to that is yes then make the first book perma-free. Why? Because the book is strong enough to act as a good entry-point for your entire series. So it’s likely that it will drive satisfying sales. If the answer to either question is no, then perma-free is probably not for you.

If your free book doesn’t rocket readers into your other books, then permafree is not a good pricing strategy.

The bottom line is this: your audience will send strong signals if your price is wrong. For instance, if you see slow sales after a successful free promo day on Amazon, then one reason could be the price point. “But I charge one buck for my ebook!” you might say.

The problem could still be with your price.

Your price may be too low.

Try jacking it up 50 cents. Yes, really. It worked for my third Shirley Link book.

One last tip is to reach out to fans. Ask them what they think the book is worth. Your readers can offer some keen insights on topics ranging from pricing to book description to, of course, story content!

How did you decide the price for your ebook? Do you experiment a lot, too?

Check out my post on how to make your book free on Amazon.

by Ben Zackheim

You may also like:

Prepare your book for its KDP Select free promotion days

Amazon KDP Select has a bridge to sell you! No, really.

The $11 Million question: Is KDP Select worth it?

Want to do more research on pricing your book? Here’s some good reading:

Smashwords survey

PBS

Nick Stephenson (with nifty graphs!)

—-

by Ben Zackheim | May 29, 2014 | Digital Identity, Writing |

NOTE: In the coming months I’m going to write about how we present ourselves online. Digital ID, as I call it, is the sum of:

After two decades of doing business online, I’ve realized that we must know who we are offline to establish the strongest Digital ID. I’ll set out to prove that thesis in my articles.

We’re all learning how to maneuver this wonderful, liberating mess together! So I look forward to hearing this community’s opinions.

—

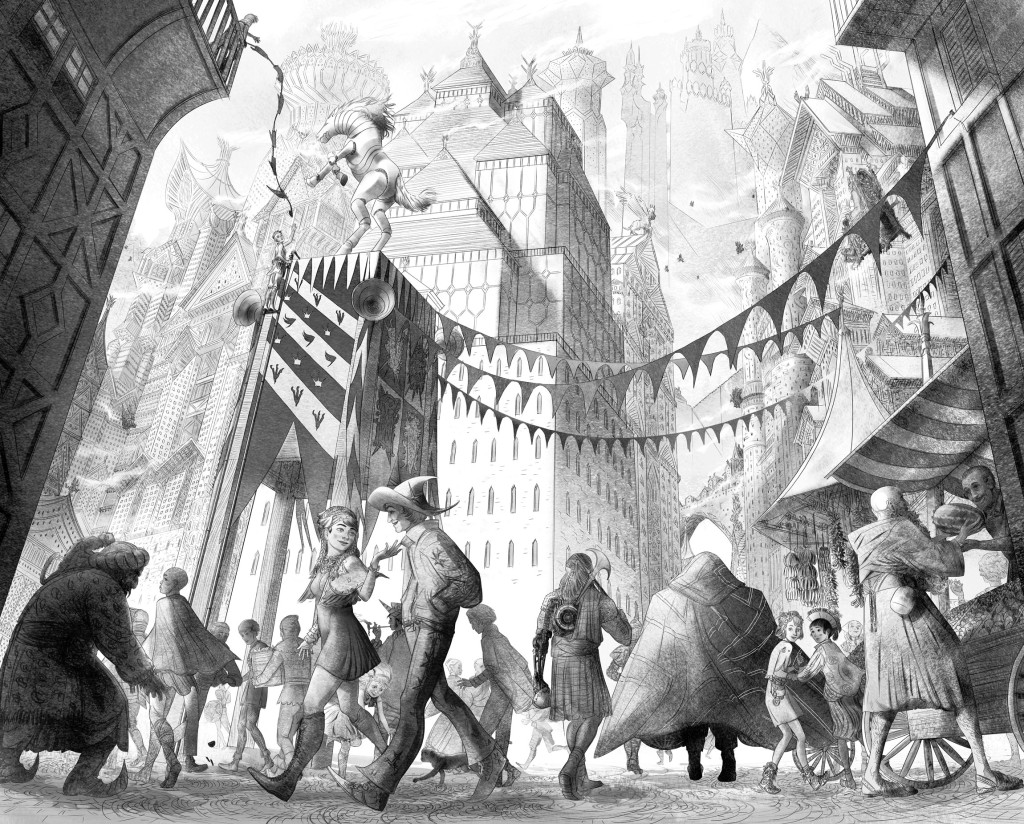

I like the image above because it’s how I feel when I wake up in the morning and put on my marketing cap and get on Facebook. I feel like I’m immersed in a pool of people, some of us connected, some of us not, some of us wanting to be connected, some of us not. And I think it’s important to recognize that mess. I think understanding how messy things are makes it easier to understand how we feel about establishing a digital ID. And, just as importantly, what we need to do to set up our own Digital ID.

What do I mean by that?

Here’s my best explanation: I’m a strong believer in the independent storyteller’s power. Not just the power of moving people to think and act and feel, but the power to find an audience on your own that you can tell your story to.

The Slow, Agonizing, Delightful Death of the Gatekeeper

For a long time, storytellers have been ruled by gatekeepers who got to tell us, “That story is good enough and worth this much. But that one sucks and good luck!”

Those days are coming to an end.

And how do I know this?

Because I was a gatekeeper.

I told some brilliant people that their stuff wouldn’t make it in today’s market. Sometimes I was right, sometimes wrong. But the powerful emotions I felt when I saw some of them move on and do great things were undeniable.

I wasn’t regretful.

I wasn’t envious.

I was inspired.

I saw them leveraging brand new tools, online services, ways of connecting that no one had thought of. They found their audience without Viacom, ESPN, AOL, Sony and all those other places where I worked.

Those gatekeepers were wrong.

I was wrong.

For my part, I had enough confidence in my own writing talent to strike out and try this new world on for size myself.

Now, the jury is still out on whether that was a good idea. While I’m doing great, I’m not making a living wage at writing my books. But I like the trajectory and I love the process. The freedom is exhilarating.

And it’s messy. Like this post’s image.

So what does this mean for working artists?

We’re living through a fundamental shift in how people learn about us and how we learn about them. As a writer looking for an audience I know in my heart that I’ll find my readers only if I stay true to myself.

To be clear, I find the incredibly detailed tracking of people by big companies creepy. I don’t trust them with the information. The counterpoint is that most of them are sharing that data with everyone. Some charge (like FB) and some don’t (like Google). Does that make it okay? I don’t know the answer to that.

I do know that I can go online and have a universe of data on my target audience at my fingertips. If I work hard, stay true to myself and my work, I can reach them and I can make a living telling my stories. The sacrifice I make is that my interests, preferences, friends and behavior is also thrown into this messy pool of data — slicing my identity into little pieces for another artist or writer or entrepreneur to scour through and evaluate.

[Tweet "I'm a data point for someone else. And they're mine."]

It’s a fascinating, liberating, terrifying time. And I’m delighted to be a part of the mess every single day.